Cancer pain

Pain in cancer may arise from a tumor compressing or infiltrating tissue; from treatments and diagnostic procedures; or from skin, nerve and other changes caused by the body's immune response or hormones released by the tumor. Most acute (short-term) pain is caused by treatment or diagnostic procedures, though radiotherapy and chemotherapy may produce painful conditions that persist long after treatment has ended.

At any given time, about half of all patients with malignant cancer are experiencing pain, and more than a third of those experience moderate or severe pain that diminishes their quality of life by adversely affecting mood, sleep, social relations and activities of daily living.[1][2] Pain is more common in the later stages of the illness.

Cancer pain can be eliminated or well controlled in 80 to 90 percent of cases by the use of drugs (such as morphine) and other interventions, but nearly one in two patients receives less-than-optimal care.

Treatment guidelines for the use of drugs in the management of cancer pain have been published by the World Health Organization (WHO)[3] and other organizations.[4] Healthcare professionals have an ethical obligation to ensure that, whenever possible, the patient or patient's guardian is well-informed about the risks and benefits associated with their pain management options. Adequate pain management may sometimes slightly shorten a dying patient's life.

Pain

The majority of patients with chronic pain notice memory and attention difficulties. Objective psychological testing has found deficits in memory, attention, cognitive processing speed, verbal ability, and mental flexibility[5] – and pain is associated with increased depression, anxiety, fear, and anger.[6] Persistent pain reduces function and overall quality of life, and is demoralizing and debilitating for patients and those who care for them.[7]

The sensation of pain is distinct from its unpleasantness. For example, it is possible through psychosurgery and some drug treatments, or by suggestion (as in hypnosis and placebo) to reduce or eliminate the unpleasantness of pain without affecting its intensity.[8]

Cancer pain is classed as acute (short term) – usually caused by medical investigation or treatment – or chronic (long-lasting).[9] About 75 percent of patients with chronic cancer pain have pain caused by the cancer itself. In most of the remainder, pain is the result of treatment.[10] Chronic pain may be continuous with occasional sharp rises in intensity (flares), or intermittent: periods of painlessness interspersed with periods of pain. Despite pain being well controlled by long-acting drugs or other treatment, flares may occasionally be felt; this is called breakthrough pain, and is treated with quick-acting analgesics.[7]

The patient's report is the best measure of pain; they will usually be asked to estimate intensity on a scale of 0–10 (with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain they have ever felt).[7]

Cause

Pain in cancer is produced by pressure on, or chemical stimulation of, specialised pain-signalling nerve endings called nociceptors (nociceptive pain), or it may be caused by damage or illness affecting nerve fibers themselves (neuropathic pain). Between 40 and 80 percent of patients with cancer pain experience neuropathic pain.[11]

Infection

Infection of a tumor or its surrounding tissue can cause rapidly escalating pain, but is sometimes overlooked as a possible cause of pain. one study[12] found that infection was the cause of pain in four percent of nearly 300 cancer patients referred for pain relief. Another report[13] described seven patients, whose previously well-controlled pain escalated significantly over several days. Antibiotic treatment produced pain relief in all patients within three days.[14]

Tumors can cause pain by crushing or infiltrating tissue, or by releasing chemicals that make nociceptors responsive to stimuli that are normally non-painful (cf. allodynia).

Vascular events

Between 15 and 25 percent of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is caused by cancer (often by a tumor compressing a vein). Cancers most likely to cause DVT are pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer, brain tumors, advanced breast cancer and advanced pelvic tumors. DVT may be the first hint that cancer is present. It causes swelling and pain (which varies from intense to vague cramp or "heaviness") in the legs, especially the calf, and (rarely) in the arms.[15]

The superior vena cava (a large vein carrying circulating, de-oxygenated blood into the heart) may be compressed by a tumor, most often non-small-cell lung carcinoma (50%), small-cell lung carcinoma (25%), lymphoma or metastases, causing superior vena cava syndrome. Common symptoms include shortness of breath, swelling of the face and neck, dilation of veins in the neck and chest, and chest wall pain.[15][16]

Nervous system

Brain tissue itself contains no nociceptors; brain tumors cause pain by pressing on blood vessels or the membrane that encapsulates the brain (the meninges), or indirectly by causing a build-up of fluid (edema) which may compress pain-sensitive tissue.[17]

Ten percent of patients with disseminated cancer develop meningeal carcinomatosis, where metastatic seedlings develop in the meninges of both the brain and spinal cord (with possible invasion of the brain or spinal cord). Melanoma and breast and lung cancer account for 90 percent of such cases. Back pain and headache – often severe and possibly associated with nausea, vomiting, neck rigidity and pain or discomfort in the eyes due to light exposure (photophobia) – are frequently the first symptoms of meningeal carcinomatosis. "Pins and needles" (paresthesia), bowel or bladder dysfunction and lower motor neuron weakness are common features.[18]

About three percent of cancer patients experience spinal cord compression, usually from expansion of the vertebral body or pedicle (fig. 1) due to metastasis, sometimes involving collapse of the vertebral body. Occasionally compression is caused by nonvertebral metastasis adjacent to the spinal cord. Compression of the long tracts of the cord itself produces funicular pain and compression of a spinal nerve root (fig. 5) produces radicular pain. Seventy percent of cases involve the thoracic, 20 percent the lumbar, and 10 percent the cervical spine; and about 20 percent of cases involve multiple sites of compression. The nature of the pain depends on the location of the compression.[14]

Infiltration or compression of a nerve by a primary tumor causes peripheral neuropathy in one to five percent of cancer patients.[14]

Small-cell lung cancer and, less often, cancer of the breast, colon or ovary may produce inflammation of the dorsal root ganglia (fig. 5), precipitating burning, tingling pain in the extremities, with occasional "lightning" or lancinating pains.[14][19]

Brachial plexopathy is a common product of Pancoast tumor, lymphoma and breast cancer, and can produce severe burning dysesthesic pain on the back of the hand, and cramping, crushing forearm pain.[14]

Bone[edit]

Invasion of bone by cancer is the most common source of cancer pain. About 70 percent of breast and prostate cancer patients, and 40 percent of those with lung, kidney and thyroid cancers develop bone metastases. It is commonly felt as tenderness, with constant background pain and instances of spontaneous or movement-related exacerbation, and is frequently described as severe. Tumors in the marrow instigate a vigorous immune response which enhances pain sensitivity, and they release chemicals that stimulate nociceptors. As they grow, tumors compress, consume, infiltrate or cut off blood supply to body tissues, which can cause pain.[14][18]

Rib fractures, common in breast, prostate and other cancers with rib metastases, can cause brief severe pain on twisting the trunk, coughing, laughing, breathing deeply or moving between sitting and lying.[14] In breast, prostate or lung cancer, multiple myeloma and some other cancers, sudden onset limb or back pain may indicate pathological bone fracture (most often in the upper femur).[15]

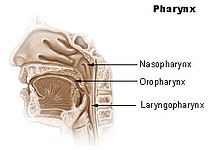

The base of the skull may be affected by metastases from cancer of the bronchus, breast or prostate, or cancer may spread directly to this area from the nasopharynx (fig. 2), and this may cause headache, facial paresthesia, dysesthesia or pain, or cranial nerve dysfunction – the exact symptoms depending on the cranial nerves impacted.[14]

Pelvis[edit]

Pain produced by cancer within the pelvis varies depending on the affected tissue, but it frequently radiates diffusely to the upper thigh, and may refer to the lumbar region. Lumbosacral plexopathy is often caused by recurrence of cancer in the presacral space, and may refer to the external genitalia or perineum. Local recurrence of cancer attached to the side of the pelvic wall may cause pain in one of the iliac fossae. Pain on walking that confines the patient to bed indicates possible cancer adherence to or invasion of the iliacus muscle. Pain in the hypogastrium (between the navel and pubic bone) is often found in cancers of the uterus and bladder, and sometimes in colorectal cancer especially if infiltrating or attached to either uterus or bladder.[14]

Viscera[edit]

Visceral pain is diffuse and difficult to locate, and is often referred to more distant, usually superficial, sites.[18]

- Liver

- Acute hemorrhage into a hepatocellular carcinoma causes severe upper right quadrant pain, and may be life-threatening, requiring emergency surgery or other emergency intervention.[15]

A tumor can expand the size of the liver several times and consequent stretching of its capsule can cause aching pain in the right hypochondrium. Other causes of pain in enlarged liver are traction of the supporting ligaments when standing or walking, the liver pressing against the rib cage or pinching the wall of the abdomen, and straining the lumbar spine. In some postures the liver may pinch the parietal peritoneum against the lower rib cage, producing sharp, transitory pain, relieved by changing position. The tumor may also infiltrate the liver's capsule, causing dull, and sometimes stabbing pain. [14]

- Kidneys and spleen

- Cancer of the kidneys and spleen produces less pain than that caused by liver tumor – kidney tumors eliciting pain only once the organ has been almost totally destroyed and the cancer has invaded the surrounding tissue or adjacent pelvis. Pressure on the kidney or ureter from a tumor outside the kidney can cause extreme flank pain.[17] Local recurrence of cancer after the removal of a kidney can cause pain in the lumbar back, or L1 or L2 spinal nerve pain in the groin or upper thigh, accompanied by weakness and numbness of the iliopsoas muscle, exacerbated by activity.[14]

- Abdominal and urogenital

- Inflammation of artery walls and tissue adjacent to nerves is common in tumors of abdominal and urogenital hollow organs.[20] Infection or cancer may irritate the trigone of the urinary bladder, causing spasm of the detrusor urinae muscle (the muscle that squeezes urine from the urinary bladder), resulting in deep pain above the pubic bone, possibly referred to the tip of the penis, lasting from a few minutes to half an hour.[14]

- Gastrointestinal

- The pain of intestinal tumors may be the result of disturbed motility, dilation, altered blood flow or ulceration. Malignant lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract can produce large tumors with significant ulceration and bleeding.[20]

- Respiratory system

- Cancer in the bronchial tree is usually painless,[20] but ear and facial pain on one side of the head has been reported in some patients. This pain is referred via the auricular branch of the vagus nerve.[14]

Fig. 3 The pancreas: 1. pancreatic head; 4. pancreatic body; 11. pancreatic tail

Fig. 3 The pancreas: 1. pancreatic head; 4. pancreatic body; 11. pancreatic tail - Pancreas

- Ten percent of patients with cancer of the pancreatic body or tail experience pain, whereas 90 percent of those with cancer of the pancreatic head will, especially if the tumor is near the hepatopancreatic ampulla. The pain appears on the left or right upper abdomen, is constant, and increases in intensity over time. It is in some cases relieved by leaning forward and heightened by lying on the stomach. Back pain may be present and, if intense, may spread left and right. Back pain may be referred from the pancreas, or may indicate the cancer has penetrated paraspinal muscle, or entered the retroperitoneum and paraaortic lymph nodes[14]

- Rectum

- A local tumor in the rectum or recurrence involving the presacral plexus may cause pain normally associated with an urgent need to defecate. This pain may, rarely, return as phantom pain after surgical removal of the rectum, though pain within a few weeks of surgical removal of the rectum is usually neuropathic pain due to the surgery (described in one study[21] as spontaneous, intermittent, mild to moderate shooting and bursting, or tight and aching), and pain emerging after three months (described as deep, sharp, aching, intense, and continuous, made worse by sitting or pressure) usually signals recurrence of the disease. The emergence of pain on standing or walking (described as "dragging" may indicate a deeper recurrence involving attachment to muscle or fascia.[14]

Serous mucosa[edit]

Carcinosis of the peritoneum may cause pain through pressure of the metastases on nerves, inflammation, or disordered visceral motility. once a tumor has penetrated or perforated hollow viscera, acute inflammation of the peritoneum appears, inducing severe abdominal pain. Pleural carcinomatosis is normally painless.[20]

Soft tissue[edit]

Invasion of soft tissue by a tumor can cause pain by inflammatory or mechanical stimulation of nociceptors, or destruction of mobile structures such as ligaments, tendons and skeletal muscles.[20]

Diagnostic procedures[edit]

In lumbar puncture a needle is inserted between two lumbar vertebrae, through the dura mater and arachnoid membrane into the space between the arachnoid membrane and the spinal cord (the subarachnoid space), and cerebrospinal fluid (CFS) is withdrawn for examination. In one study, 14 percent of patients felt pain on lumbar puncture.[22]

In some patients, subsequent leakage of CSF through the puncture causes reduced CSF levels in the brain and spinal cord, leading to the development of post-dural-puncture headache hours or days later (66 percent within 48 hours, 90 percent within three days). It occurs so rarely immediately after puncture that other possible causes should be investigated when it does. The headache is severe and described as "searing and spreading like hot metal," involving the back and front of the head, and spreading to the neck and shoulders, sometimes involving neck stiffness. It is exacerbated by movement, sitting or standing, and relieved to some degree by lying down. Nausea, vomiting, pain in arms and legs, hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, dizziness and paraesthesia of the scalp are common. [23]

[edit]

Potentially painful interventions in cancer treatment include immunotherapy which may produce joint or muscle pain; radiotherapy, which can cause skin reactions, enteritis, fibrosis, myelopathy, bone necrosis, neuropathy or plexopathy; chemotherapy, often associated with mucositis, joint pain, muscle pain, peripheral neuropathy and abdominal pain due to diarrhea or constipation; hormone therapy, which sometimes causes pain flares; targeted therapies, such as trastuzumab and rituximab, which can cause muscle, joint or chest pain; angiogenesis inhibitors like bevacizumab, known to sometimes cause bone pain; and surgery, which may produce post-operative pain, post-amputation pain or pelvic floor myalgia. Some diagnostic procedures, such as venipuncture, paracentesis, and thoracentesis can be painful.[24]

Chemotherapy[edit]

Chemotherapy may cause mucositis, muscle pain, joint pain, abdominal pain caused by diarrhea or constipation, and peripheral neuropathy[24]

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy[edit]

Between 30 and 40 percent of patients undergoing chemotherapy experience chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): tingling numbness, intense pain, and hypersensitivity to cold, beginning in the hands and feet and sometimes progressing to the arms and legs.[25] Chemotherapy drugs associated with CIPN include thalidomide, the epothilones such as ixabepilone, the vinca alkaloids vincristine and vinblastine, the taxanes paclitaxel and docetaxel, the proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib, and the platinum-based drugs cisplatin, oxaliplatin and carboplatin.[25][26][27] Whether CIPN arises, and to what degree, is determined by the choice of drug, duration of use, the total amount consumed and whether the patient already has peripheral neuropathy. Though the symptoms are mainly sensory – pain, tingling, numbness and temperature sensitivity – in some cases motor nerves are affected, and occasionally, also, the autonomic nervous system.[28]

CIPN often follows the first chemotherapy dose and increases in severity as treatment continues, but this progression usually levels off at completion of treatment. The platinum-based drugs are the exception; with these drugs, sensation may continue to deteriorate for several months after the end of treatment.[29] Some CIPN appears to be irreversible.[29] Pain can often be helped with drug or other treatment but the numbness is usually resistant to treatment.[30]

CIPN disrupts leisure, work and family relations, and the pain of CIPN is often accompanied by sleep and mood disturbance, fatigue and functional difficulties. A 2007 American study found that most patients did not recall being told to expect CIPN, and doctors monitoring the condition rarely asked how it affects daily living but focused on practical effects such as dexterity and gait.[31] It is not known what causes the condition, but microtubule and mitochondrial damage, and leaky blood vessels near nerve cells are some of the possibilities being explored. It is unknown what percentage of patients are affected.[29]

As possible preventative interventions, the American National Cancer Institute Symptom Management and Health-related Quality of Life Steering Committee recommends continued investigation of glutathione, and intravenous calcium and magnesium, which have shown early promise in limited human trials; acetyl-L-carnitine, which was effective in animal models and on diabetes and HIV patients; and the anti-oxidant alpha-lipoic acid.[25]

Mucositis[edit]

Cancer drugs can cause changes in the biochemistry of mucous membranes resulting in intense pain in the mouth, throat, nasal passages, and gastrointestinal tract. This pain can make talking, drinking, or eating difficult or impossible.[32]

Muscle and joint pain[edit]

Withdrawal of steroid medication can cause joint pain and diffuse muscle pain accompanied by fatigue; these symptoms resolve with recommencement of steroid therapy. Chronic steroid therapy can result in aseptic necrosis of the humoral or femoral head, resulting in shoulder or knee pain described as dull and aching, and reduced movement in or inability to use arm or hip. Aromatase inhibitors can cause diffuse muscle and joint pain and stiffness, and may increase the likelihood of osteoporosis and consequent fractures.[32]

Radiotherapy[edit]

Radiotherapy may affect the connective tissue surrounding nerves, and may damage or kill white or gray matter in the brain or spinal cord.

Fibrosis around the brachial or lumbosacral plexus[edit]

Radiotherapy may produce excessive growth of the fibrous tissue enveloping the brachial plexus or lumbosacral plexus, which can result in damage to the nerves over time (6 months to 20 years). This nerve damage may cause numbness, "pins and needles" (dysesthesia) and weakness in the affected limb. If pain develops, it is described as diffuse, severe, burning pain, increasing over time, in part or all of the affected limb.[32]

Spinal cord damage[edit]

If radiotherapy includes the spinal cord, changes may occur which do not become apparent until some time after treatment. "Early delayed radiation-induced myelopathy" can manifest from six weeks to six months after treatment; the usual symptom is a Lhermitte sign ("a brief, unpleasant sensation of numbness, tingling and often electric-like discharge going from the neck to the spine and extremities, triggered by neck flexion"), usually followed by improvement two to nine months after onset, though in some cases symptoms persist for a long time. "Late delayed radiation-induced myelopathy" may occur six months to ten years after treatment. The typical presentation is Brown-Séquard syndrome (a motor deficit and numbness to touch and vibration on one side of the body and loss of pain and temperature sensation on the other). onset may be sudden but is usually progressive. Some patients improve and others deteriorate.[33]

Management[edit]

Cancer pain treatment is directed toward relieving pain with minimal adverse treatment effects, allowing the patient a good quality of life and level of function and a relatively painless death.[34] Though 80–90 percent of cancer pain can be eliminated or well controlled, nearly half of all patients with cancer pain (including those in developed countries) receive less than optimal care.[35]

Cancer is a dynamic process, and pain interventions need to reflect this. Several different treatment modalities may be required over time, as the disease progresses. Pain managers should clearly explain to the patient the cause of the pain and the various treatment possibilities, and should consider, as well as drug therapy, directly modifying the underlying disease, raising the pain threshold, interrupting, destroying or stimulating pain pathways, and suggesting lifestyle modification.[34] The relief of psychological, social and spiritual distress is a key element in effective pain management.[3]

If a patient's pain cannot be well controlled, they should be referred to a palliative care or pain management specialist or clinic.[7]

Psychological[edit]

Coping strategies[edit]

How a person responds to pain affects the intensity of pain (moderately), the degree of disability they experience, and the impact of pain on their quality of life. Strategies employed by patients to cope with pain include enlisting the help of others, persisting with tasks despite pain, distraction, rethinking maladaptive ideas, and prayer or ritual.[36]

Some people in pain tend to focus on and exaggerate the threat value of painful stimuli, and estimate their own ability to deal with pain as poor. This tendency is termed "catastrophizing."[37] The few studies so far conducted into catastrophizing in cancer pain have suggested that it is associated with higher levels of pain and psychological distress. Cancer pain patients who accept that pain will persist and nevertheless are able to engage in a meaningful life were less susceptible to catastrophizing and depression in one study. Patients who are usually high in the trait, "hope" (defined as the ability to see pathways to desired goals coupled with the motivation to use those pathways), were found in two studies to experience much lower levels of pain, fatigue and depression.[36]

Patients who are confident in their understanding of their condition and its treatment, and confident in their ability to (a) control their symptoms, (b) collaborate successfully with their informal carers and (c) communicate effectively with health care providers experience better pain outcomes. Physicians should therefore take steps to encourage and facilitate effective patient communication, and should consider psychosocial intervention.[36]

Psychosocial interventions[edit]

Psychosocial interventions do affect the amount of pain experienced and the degree to which it interferes with daily life,[38] and the American Institute of Medicine[39] and the American Pain Society[40] support the inclusion of expert, quality-controlled psychosocial care as part of cancer pain management. Psychosocial interventions include education (addressing among other things the correct use of analgesic medications and effective communication with clinicians),[2] which modestly but reliably reduces the amount of pain experienced by the patient, and coping-skills training (changing thoughts, emotions, and behaviors through training in skills such as problem solving, relaxation, distraction and cognitive restructuring), which reduces psychological distress and improves quality of life in cancer patients. Education may be more helpful to patients with stage I cancer and their carers, and coping-skills training may be more helpful at stages II and III.[36]

The patient's adjustment to cancer depends vitally on the support of their partner and other informal carers, but pain can seriously disrupt such interpersonal relationships, so patients and therapists should consider involving partners and other informal carers in expert, quality-controlled psychosocial therapeutic interventions.[36]

Medications[edit]

The WHO guidelines[3] recommend prompt oral administration of drugs when pain occurs, starting, if the patient is not in severe pain, with non-opioid drugs such as paracetamol, dipyrone, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or COX-2 inhibitors.[3] Then, if complete pain relief is not achieved or disease progression necessitates more aggressive treatment, mild opioids such as codeine, dextropropoxyphene, dihydrocodeine or tramadol are added to the existing non-opioid regime. If this is or becomes insufficient, mild opioids are replaced by stronger opioids such as morphine, while continuing the non-opioid therapy, escalating opioid dose until the patient is painless or the maximum possible relief without intolerable side effects has been achieved. If the initial presentation is severe cancer pain, this stepping process should be skipped and a strong opioid should be started immediately in combination with a non-opioid analgesic.[34]

The usefulness of the second step (mild opioids) is being debated in the clinical and research communities. Some authors challenge the pharmacological validity of the step and, pointing to their higher toxicity and low efficacy, argue that mild opioids could be replaced by small doses of strong opioids (with the possible exception of tramadol due to its demonstrated efficacy in cancer pain, its specificity for neuropathic pain, and its low sedative properties and reduced potential for respiratory depression in comparison to conventional opioids).[34]

Antiemetic and laxative treatment should be commenced concurrently with strong opioids, to counteract the usual nausea and constipation. Nausea normally resolves after two or three weeks of treatment but laxatives will need to be aggressively maintained. More than half of patients with advanced cancer and pain will need strong opioids, and these in combination with non-opioids can produce acceptable analgesia in 70–90 percent of cases. Sedation and cognitive impairment usually occur with the initial dose or a significant increase in dosage of a strong opioid, but improve after a week or two of consistent dosage.[34]

Analgesics should not be taken on demand" but "by the clock" (every 3–6 hours), with each dose delivered before the preceding dose has worn off, in doses sufficiently high to ensure continuous pain relief. Patients taking slow-release morphine should also be provided with immediate-release ("rescue") morphine to use as necessary, for pain spikes (breakthrough pain) that are not suppressed by the regular medication.[34]

Oral analgesia is the cheapest, simplest and most acceptable mode of delivery. Other delivery routes such as sublingual, topical, parenteral, rectal or spinal should be considered if the need is urgent, or in case of vomiting, impaired swallow, obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract, poor absorption or coma.[34]

Liver and kidney disease can affect the biological activity of analgesics. When such patients are treated with oral opioids they must be monitored for the possible need to reduce dose, extend dosing intervals, or switch to other opioids or other modes of delivery.[34] Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be especially beneficial in some pain conditions but their benefit should be weighed against their gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal risks.[10]

Not all pain yields completely to classic analgesics, and drugs that are not traditionally considered analgesics but which reduce pain in some cases, such as steroids or bisphosphonates, may be employed concurrently with analgesics at any stage. Tricyclic antidepressants, class I antiarrhythmics, or anticonvulsants are the drugs of choice for neuropathic pain. Up to 90 percent of patients at death are using such "adjuvants". Many adjuvants carry a significant risk of serious complications.[34]

Anxiety reduction can reduce the unpleasantness of pain but is least effective for moderate and severe pain.[41] Since anxiolytics such as benzodiazepines and major tranquilizers add to sedation, they should only be used to address anxiety, depression, disturbed sleep or muscle spasm.[34]

Interventional[edit]

If the analgesic and adjuvant regimen recommended above does not adequately relieve pain, additional modes of intervention are available.[42]

Radiation[edit]

Radiotherapy is used when drug treatment is failing to control the pain of a growing tumor, such as in bone metastisis (most commonly), penetration of soft tissue, or compression of sensory nerves. Often, low doses are adequate to produce analgesia, thought to be due to reduction in pressure or, possibly, interference with the tumor's production of pain-promoting chemicals.[43] Radiopharmaceuticals that target specific tumors have been used to treat the pain of metastatic illnesses. Relief may occur within a week of treatment and may last from two to four months.[42]

Nerve blocks[edit]

Neurolysis is the injury of a nerve. Chemicals, laser, freezing or heating may be used to injure a sensory nerve and so produce degeneration of the nerve's fibers and the fibers' myelin sheaths, and temporary interference with the transmission of pain signals. In this procedure, the protective casing around the myelin sheath, the basal lamina, is preserved so that, as a damaged fiber (and its myelin sheath) regrows, it travels within its basal lamina and connects with the correct loose end, and function may be restored. Surgical cutting of a nerve severs the basal laminae, and without these tubes to channel the regrowing fibers to their lost connections, deafferentation pain (spontaneous pain due to loss of signal to the spinal cord) may develop. This is why neurolysis is preferred over surgically blocking nerves.[44] A brief "rehearsal" block using local anesthesia should be tried before the actual neurolytic block, to determine efficacy and detect side effects.[42] The aim of this treatment is pain elimination, or the reduction of pain to the point where opioids may be effective.[42] Though neurolysis lacks long-term outcome studies and evidence-based guidelines for its use, for patients with progressive cancer and otherwise incurable pain, it can play an essential role.[44]

Targets for neurolytic block include the celiac plexus, most commonly for cancer of the gastrointestinal tract up to the transverse colon, and pancreatic cancer, but also for stomach cancer, gall bladder cancer, adrenal mass, common bile duct cancer, chronic pancreatitis and active intermittent porphyria; the splanchnic nerve, for retroperitoneal pain, and similar conditions to those addressed by the celiac plexus block but, because of its higher rate of complications, used only if the celiac plexus block is not producing adequate relief; hypogastric plexus, for cancer of the descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum, as well as cancers of the bladder, prostatic urethra, prostate, seminal vesicles, testicles, uterus, ovary and vaginal fundus (the inner end of the vagina); ganglion impar, for the perinium, vulva, anus, distal (outer end of the) rectum, distal urethra, and distal third of the vagina; the stellate ganglion, usually for head and neck cancer or sympathetically mediated arm and hand pain; the intercostal nerves, which serve the skin of the chest and abdomen; and a dorsal root ganglion may be injured by targeting the root inside the subarachnoid cavity (fig.5), most effective for pain in the chest or abdominal wall, but also used for other areas including arm/hand or leg/foot pain.[42]

Cutting or destruction of nervous tissue[edit]

Surgical cutting or destruction of peripheral or central nervous tissue is now rarely used in the treatment of pain.[42] Procedures include neurectomy, cordotomy, dorsal root entry zone lesioning, and cingulotomy.

Neurectomy involves cutting a nerve, and is (rarely) used in patients with short life expectancy who are unsuitable for drug therapy due to ineffectiveness or intolerance. The dorsal (sensory) root or dorsal root ganglion may be usefully targeted (called rhizotomy); with the dorsal root ganglion possibly the more effective target because some sensory fibers enter the spinal cord from the dorsal root ganglion via the ventral (motor) root, and these would not be interrupted by dorsal root neurectomy. Because nerves often carry both sensory and motor fibers, motor impairment is a possible side effect of neurectomy. A common result of this procedure is "deafferentation pain" where, 6–9 months after surgery, pain returns at greater intensity.[45]

Cordotomy involves cutting into the spinothalamic tracts, which run up the front/side (anterolateral) quadrant of the spinal cord, carrying heat and pain signals to the brain (fig. 6). Pancoast tumor pain has been effectively treated with dorsal root entry zone (DREZ) lesioning – destruction of a region of the spinal cord where peripheral pain signals cross to spinal cord fibers – this is major surgery, carrying the risk of significant neurological side effects. Cingulotomy involves cutting the fibers that carry signals directly from the cingulate gyrus to the entorhinal cortex in the brain. It reduces the unpleasantness of pain (without affecting its intensity), but may have cognitive side effects.[45]

Intrathecal programmable pump[edit]

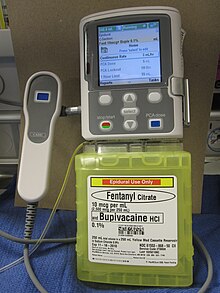

Delivery of an opioid such as morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl, sufentanyl and meperidine directly into the subarachnoid cavity (fig. 5) provides enhanced analgesia with reduced systemic side effects, and has reduced the level of pain in otherwise intractable cases. The anxiolytic clonidine or the nonopioid analgesic ziconotide, and local anesthetics such as bupivacaine, ropivacaine or tetracaine may also be infused along with the opioid.[42][45]

Long-term epidural catheter[edit]

The outer layer of the sheath surrounding the spinal cord is called the dura mater (fig.5). Between this and the surrounding vertebrae is the epidural space, filled with connective tissue, fat and blood vessels, and crossed by the spinal nerve roots. A catheter may be inserted into this space for three to six months, to deliver anesthetics or analgesics. The line carrying the drug may be threaded under the skin to emerge at the front of the patient, a process called tunneling, and this is recommended with long term use so as to reduce the chance of any infection at the exit site reaching the epidural space.[42]

Spinal cord stimulation[edit]

Electrical stimulation of the dorsal columns of the spinal cord (fig. 6) can produce analgesia. First, the leads are implanted, guided by the patient's report and fluoroscopy, and the generator is worn externally for several days to assess efficacy. If pain is reduced by more than half, the therapy is deemed to be suitable. A small pocket is cut into the tissue beneath the skin of the upper buttocks, chest wall or abdomen and the leads are threaded under the skin from the stimulation site to the pocket, where they are attached to the snugly-fitting generator.[45] It seems to be more helpful with neuropathic and ischemic pain than nociceptive pain, and is not often used in the treatment of cancer pain.[46]

Deep brain stimulation[edit]

Ongoing electrical stimulation of structures deep within the brain – the periaqueductal gray and periventricular gray for nociceptive pain, and the internal capsule, ventral posterolateral nucleus and ventral posteromedial nucleus for neuropathic pain – has produced impressive results with some patients but results vary and appropriate patient selection is important. one study[47] of seventeen patients with intractable cancer pain found that thirteen were virtually painless and only four required opioid analgesics on release from hospital after the intervention. Most ultimately did resort to opioids, usually in the last few weeks of life.[46]

Hypophysectomy[edit]

Hypophysectomy is the destruction of the pituitary gland, and has been used successfully on metastatic breast and prostate cancer pain.[45]

Complimentary and alternative medicine[edit]

Due to the poor quality of most studies of complementary and alternative medicine in relief of cancer pain, it is not possible to recommend integration of these therapies into the management of cancer pain. There is weak evidence for a modest benefit from hypnosis; studies of massage therapy produced mixed results and none found pain relief after 4 weeks; Reiki, and touch therapy results were inconclusive; acupuncture, the most studied such treatment, has demonstrated no benefit as an adjunct analgesic in cancer pain; the evidence for music therapy is equivocal; and some herbal interventions such as PC-SPES, mistletoe, and saw palmetto are known to be toxic to some cancer patients. The most promising evidence, though still weak, is for mind-body interventions such as biofeedback and relaxation techniques.[7]

Barriers to treatment[edit]

Despite the publication and ready availability of simple and effective evidence-based pain management guidelines by the World Health Organization (WHO)[3] and others,[4] many medical care providers lack a broad and deep understanding of key aspects of pain management, including assessment, dosing, tolerance, addiction, and side effects, and many do not know that pain can be well controlled in most cases.[31][34] In Canada, for instance, veterinarians get five times more training in pain than do physicians, and three times more training than nurses.[48] Physicians may undertreat pain due to fear of being audited by a regulatory body.[7]

Systemic institutional problems in the delivery of pain management include lack of resources for adequate training of physicians, time constraints, failure to refer patients for pain management in the clinical setting, inadequate insurance reimbursement for pain management, lack of sufficient stocks of pain medicines in poorer areas, outdated government policies on cancer pain management, and excessively complex or restrictive government and institutional regulations on the prescription, supply, and administration of opioid medications.[7][31][34]

Patients may not report pain due to costs of treatment, a belief that pain is inevitable, an aversion to treatment side effects, fear of developing addiction or tolerance, fear of distracting the doctor from treating the illness,[31] or fear of masking a symptom that is important for monitoring progress of the illness. Patients may be reluctant to take adequate pain medicine because they are unaware of their prognosis, or may be unwilling to accept their diagnosis.[49] Patient failure to report pain or misguided reluctance to take pain medicine can be overcome by sensitive coaching.[31][34]

Epidemiology[edit]

Fifty three percent of all patients with cancer, 59 percent of patients receiving anticancer treatment, 64 percent of patients with metastatic or advanced-stage disease, and 33 percent of patients after completion of curative treatment experience pain.[50] Evidence for prevalence of pain in newly diagnosed cancer is scarce. one study found pain in 38 percent of newly diagnosed cases, another found 35 percent of new patients had experienced pain in the preceding two weeks, while another reported that pain was an early symptom in 18–49 percent of cases. More than one third of patients with cancer pain describe the pain as moderate or severe.[50]

Primary tumors in the following locations are associated with a relatively high prevalence of pain:[51][52]

- Head and neck (67 to 91 percent)

- Prostate (56 to 94 percent)

- Uterus (30 to 90 percent)

- The genitourinary system (58 to 90 percent)

- Breast (40 to 89 percent)

- Pancreas (72 to 85 percent)

- Esophagus (56 to 94 percent)

All patients with advanced multiple myeloma and advanced sarcoma are likely to experience pain.[52]

Legal and ethical considerations[edit]

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights obliges signatory nations to make pain treatment available to those within their borders as a duty under the human right to health. A failure to take reasonable measures to relieve the suffering of those in pain may be seen as failure to protect against inhuman and degrading treatment under Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[53] The right to adequate palliative care has been affirmed by the US Supreme Court in two cases, Vacco v. Quill and Washington v. Glucksberg, which were decided in 1997.[54] This right has also been confirmed in statutory law, such as in the California Business and Professional Code 22, and in other case law precedents in circuit courts and in other reviewing courts in the US.[55] The 1994 Medical Treatment Act of the Australian Capital Territory states that a "patient under the care of a health professional has a right to receive relief from pain and suffering to the maximum extent that is reasonable in the circumstances".[53]

Doctors and nurses have an ethical obligation to ensure that when consent for pain treatment is withheld or given it is, whenever possible, withheld or given by a fully informed patient. Most importantly, patients must be apprised of any serious risks and the common side effects of pain treatments. What appears to be an obviously acceptable risk or harm to a professional may be unacceptable to the patient. For instance, patients who experience pain on movement may be willing to forgo strong opioids in order to enjoy alertness during their painless periods, whereas others would choose around-the-clock sedation so as to remain pain-free. Well-informed patients who communicate and work well with their medical providers are more likely to achieve an optimum pain management regimen. The care provider should not insist on treatment that the patient rejects, and must not provide treatment that the provider believes is more harmful or riskier than the possible benefits can justify.[49]

Some patients – particularly those who are terminally ill – may not wish to be involved in making pain management decisions, and may delegate such choices to their treatment providers. The patient's participation is a right, not an obligation, and although reduced patient involvement may result in less-than-optimal pain management, their choice should be respected.[49]

As medical professionals become better informed about the interdependent relationship between physical, emotional, social, and spiritual pain, and the demonstrated benefit to physical pain from alleviation of these other forms of suffering, they may be inclined to question the patient and family about interpersonal relationships. Unless the patient has asked for such psychosocial intervention – or at least freely consented to such questioning – this would be an ethically unjustifiable intrusion into the patient's personal affairs (analogous to providing drugs without the patient's informed consent).[49]

The obligation of a professional medical care provider to alleviate suffering may occasionally come into conflict with the obligation to prolong life. If a terminally ill patient prefers to be painless, despite a high level of sedation and a risk of shortening their life, they should be provided with their desired pain relief (despite the cost of sedation and a possibly slightly shorter life). Where a patient is unable to be involved in this type of decision, the law and the medical profession in the United Kingdom allow the doctor to assume that the patient would prefer to be painless, and thus the provider may prescribe and administer adequate analgesia, even if the treatment may slightly hasten death. It is taken that the underlying cause of death in this case is the illness and not the necessary pain management.[49]

One philosophical justification for the aforementioned legal approach is the doctrine of double effect, where to justify an act involving both a good and a bad effect, four conditions are necessary:

- the act must be good overall (or at least morally neutral)

- the person acting must intend only the good effect, with the bad effect considered an unwanted side effect

- the bad effect must not be the cause of the good effect

- the good effect must outweigh the bad effect.

Just as an oncologist who intends to treat cancer may foresee but not intend causing nausea, so a doctor treating suffering may see the risk of, but not intend, slightly shortening the patient's life.[49][56]

Cited works[edit]

'건강하고 행복하게 > Good Life' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 암은 병이 아니고 다른 병의 증상일 뿐이다. (0) | 2013.06.30 |

|---|---|

| Lymph system (0) | 2013.06.18 |

| Death Isn’t What It Appears To Be - By Andreas Moritz (0) | 2013.06.13 |

| Andreas Moritz - The Mysterious Death of a Legend (0) | 2013.06.13 |

| 오래 살려면 (0) | 2013.04.21 |