Karl Marx[6] ( 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, political theorist, sociologist, journalist and revolutionary socialist. 1800년대 사람이다.

Born in Trier to a middle-class family, Marx later studied political economy and Hegelian philosophy. As an adult, Marx became stateless and spent much of his life in London, where he continued to develop his thought in collaboration with German thinker Friedrich Engels and published various works.

His two most well-known are the 1848 pamphlet The Communist Manifesto 30세에 발표 and the three-volume Das Kapital. His work has since influenced subsequent intellectual, economic and political history.

Marx's theories about society, economics and politics—collectively understood as Marxism—hold that human societies develop through class struggle. In capitalism, this manifests itself in the conflict between the ruling classes (known as the bourgeoisie) that control the means of production and working classes (known as the proletariat) that enable these means by selling their labour power in return for wages.[8] Employing a critical approach known as historical materialism,

Marx predicted that, like previous socioeconomic systems, capitalism produced internal tensions which would lead to its self-destruction and replacement by a new system: socialism.

For Marx, class antagonisms under capitalism, owing in part to its instability and crisis-prone nature, would eventuate the working class' development of class consciousness, leading to their conquest of political power and eventually the establishment of a classless, communist society constituted by a free association of producers.[9]

Marx actively pressed for its implementation, arguing that the working class should carry out organised revolutionary action to topple capitalism and bring about socio-economic emancipation.[10]

Marx has been described as one of the most influential figures in human history and his work has been both lauded and criticised.[11] His work in economics laid the basis for much of the current understanding of labour and its relation to capital, and subsequent economic thought.[12][13][14][15] Many intellectuals, labour unions, artists and political parties worldwide have been influenced by Marx's work, with many modifying or adapting his ideas.

Marx is typically cited as one of the principal architects of modern social science.[16][17]

Thought[edit]

Influences[edit]

Marx's view of history, which came to be called historical materialism (controversially adapted as the philosophy of dialectical materialism by Engels and Lenin), certainly shows the influence of Hegel's claim that one should view reality (and history) dialectically.[202] However, Hegel had thought in idealist terms, putting ideas in the forefront, whereas Marx sought to rewrite dialectics in materialist terms, arguing for the primacy of matter over idea.[81][202]Where Hegel saw the "spirit" as driving history, Marx saw this as an unnecessary mystification, obscuring the reality of humanity and its physical actions shaping the world.[202] He wrote that Hegelianism stood the movement of reality on its head, and that one needed to set it upon its feet.[202] Despite his dislike of mystical terms, Marx used Gothic language in several of his works and in The Capital he refers to capital as "necromancy that surrounds the products of labour".[208

Though inspired by French socialist and sociological thought,[203] Marx criticised utopian socialists, arguing that their favoured small-scale socialistic communities would be bound to marginalisation and poverty and that only a large-scale change in the economic system can bring about real change.[205]

The other important contribution to Marx's revision of Hegelianism came from Engels's book, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, which led Marx to conceive of the historical dialectic in terms of class conflict and to see the modern working class as the most progressive force for revolution.[4]

Marx believed that he could study history and society scientifically and discern tendencies of history and the resulting outcome of social conflicts. Some followers of Marx therefore concluded that a communist revolution would inevitably occur. However, Marx famously asserted in the eleventh of his "Theses on Feuerbach" that "philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point however is to change it" and he clearly dedicated himself to trying to alter the world.[10][198]

Philosophy and social thought[edit]

Marx's polemic with other thinkers often occurred through critique and thus he has been called "the first great user of critical method in social sciences".[202][203]He criticised speculative philosophy, equating metaphysics with ideology.[209] By adopting this approach, Marx attempted to separate key findings from ideological biases.[203] This set him apart from many contemporary philosophers.[10]

Human nature[edit]

Like Tocqueville, who described a faceless and bureaucratic despotism with no identifiable despot,[210] Marx also broke with classical thinkers who spoke of a single tyrant and with Montesquieu, who discussed the nature of the single despot. Instead, Marx set out to analyse "the despotism of capital".[211] Fundamentally, Marx assumed that human history involves transforming human nature, which encompasses both human beings and material objects.[212]Humans recognise that they possess both actual and potential selves.[213][214] For both Marx and Hegel, self-development begins with an experience of internal alienation stemming from this recognition, followed by a realisation that the actual self, as a subjective agent, renders its potential counterpart an object to be apprehended.[214] Marx further argues that by moulding nature[215] in desired ways[216] the subject takes the object as its own and thus permits the individual to be actualised as fully human. For Marx, the human nature—Gattungswesen, or species-being—exists as a function of human labour.[213][214][216] Fundamental to Marx's idea of meaningful labour is the proposition that in order for a subject to come to terms with its alienated object it must first exert influence upon literal, material objects in the subject's world.[217] Marx acknowledges that Hegel "grasps the nature of work and comprehends objective man, authentic because actual, as the result of his own work",[218] but characterises Hegelian self-development as unduly "spiritual" and abstract.[219] Marx thus departs from Hegel by insisting that "the fact that man is a corporeal, actual, sentient, objective being with natural capacities means that he has actual, sensuous objects for his nature as objects of his life-expression, or that he can only express his life in actual sensuous objects".[217] Consequently, Marx revises Hegelian "work" into material "labour" and in the context of human capacity to transform nature the term "labour power".[81]

Labour, class struggle and false consciousness[edit]

Marx had a special concern with how people relate to their own labour power.[221] He wrote extensively about this in terms of the problem of alienation.[222] As with the dialectic, Marx began with a Hegelian notion of alienation but developed a more materialist conception.[221] Capitalism mediates social relationships of production (such as among workers or between workers and capitalists) through commodities, including labour, that are bought and sold on the market.[221] For Marx, the possibility that one may give up ownership of one's own labour—one's capacity to transform the world—is tantamount to being alienated from one's own nature and it is a spiritual loss.[221] Marx described this loss as commodity fetishism, in which the things that people produce, commodities, appear to have a life and movement of their own to which humans and their behaviour merely adapt.[223]

Commodity fetishism provides an example of what Engels called "false consciousness",[224] which relates closely to the understanding of ideology. By "ideology", Marx and Engels meant ideas that reflect the interests of a particular class at a particular time in history, but which contemporaries see as universal and eternal.[225] Marx and Engels's point was not only that such beliefs are at best half-truths, as they serve an important political function. Put another way, the control that one class exercises over the means of production includes not only the production of food or manufactured goods, but also the production of ideas (this provides one possible explanation for why members of a subordinate class may hold ideas contrary to their own interests).[81][226] An example of this sort of analysis is Marx's understanding of religion, summed up in a passage from the preface[227] to his 1843 Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right:

Whereas his Gymnasium senior thesis at the Gymnasium zu Trier argued that religion had as its primary social aim the promotion of solidarity, here Marx sees the social function of religion in terms of highlighting/preserving political and economic status quo and inequality.[229]

Marx was an outspoken opponent of child labour,[230] saying that British industries "could but live by sucking blood, and children’s blood too", and that U.S. capital was financed by the "capitalized blood of children".[231][232]

Economy, history and society[edit]

Marx's thoughts on labour were related to the primacy he gave to the economic relation in determining the society's past, present and future (see also economic determinism).[202][205][233] Accumulation of capital shapes the social system.[205] For Marx, social change was about conflict between opposing interests, driven in the background by economic forces.[202] This became the inspiration for the body of works known as the conflict theory.[233] In his evolutionary model of history, he argued that human history began with free, productive and creative work that was over time coerced and dehumanised, a trend most apparent under capitalism.[202] Marx noted that this was not an intentional process, rather no individual or even state can go against the forces of economy.[205]

The organisation of society depends on means of production. Literally, those things, like land, natural resources and technology, necessary for the production of material goods and the relations of production. In other words, the social relationships people enter into as they acquire and use the means of production.[233]Together, these compose the mode of production and Marx distinguished historical eras in terms of distinct modes of production. Marx differentiated between base and superstructure, with the base (or substructure) referring to the economic system and superstructure, to the cultural and political system.[233] Marx regarded this mismatch between (economic) base and (social) superstructure as a major source of social disruption and conflict.[233]

Despite Marx's stress on critique of capitalism and discussion of the new communist society that should replace it, his explicit critique of capitalism is guarded, as he saw it as an improved society compared to the past ones (slavery and feudal).[81] Marx also never clearly discusses issues of morality and justice, although scholars agree that his work contained implicit discussion of those concepts.[81]

Marx's view of capitalism was two-sided.[81][150] On one hand, in the 19th century's deepest critique of the dehumanising aspects of this system he noted that defining features of capitalism include alienation, exploitation and recurring, cyclical depressions leading to mass unemployment, while on the other hand capitalism is also characterised by "revolutionising, industrialising and universalising qualities of development, growth and progressivity" (by which Marx meant industrialisation, urbanisation, technological progress, increased productivity and growth, rationality and scientific revolution) that are responsible for progress.[81][150][202] Marx considered the capitalist class to be one of the most revolutionary in history because it constantly improved the means of production, more so than any other class in history and was responsible for the overthrow of feudalismand its transition to capitalism.[205][234] Capitalism can stimulate considerable growth because the capitalist can and has an incentive to reinvest profits in new technologies and capital equipment.[221]

According to Marx, capitalists take advantage of the difference between the labour market and the market for whatever commodity the capitalist can produce. Marx observed that in practically every successful industry, input unit-costs are lower than output unit-prices. Marx called the difference "surplus value" and argued that this surplus value had its source in surplus labour, the difference between what it costs to keep workers alive and what they can produce.[81] Marx's dual view of capitalism can be seen in his description of the capitalists: he refers to them as vampires sucking worker's blood, but at the same time[202]he notes that drawing profit is "by no means an injustice"[81] and that capitalists simply cannot go against the system.[205] The true problem lies with the "cancerous cell" of capital, understood not as property or equipment, but the relations between workers and owners—the economic system in general.[205]

At the same time, Marx stressed that capitalism was unstable and prone to periodic crises.[95] He suggested that over time capitalists would invest more and more in new technologies and less and less in labour.[81] Since Marx believed that surplus value appropriated from labour is the source of profits, he concluded that the rate of profit would fall even as the economy grew.[171] Marx believed that increasingly severe crises would punctuate this cycle of growth, collapse and more growth.[171] Moreover, he believed that in the long-term, this process would necessarily enrich and empower the capitalist class and impoverish the proletariat.[171][205] In section one of The Communist Manifesto, Marx describes feudalism, capitalism and the role internal social contradictions play in the historical process:

Marx believed that those structural contradictions within capitalism necessitate its end, giving way to socialism, or a post-capitalistic, communist society:

Thanks to various processes overseen by capitalism, such as urbanisation, the working class, the proletariat, should grow in numbers and develop class consciousness, in time realising that they have to and can change the system.[202][205] Marx believed that if the proletariat were to seize the means of production, they would encourage social relations that would benefit everyone equally, abolishing exploiting class and introduce a system of production less vulnerable to cyclical crises.[202] Marx argued in The German Ideology that capitalism will end through the organised actions of an international working class:

In this new society, the self-alienation would end and humans would be free to act without being bound by the labour market.[171] It would be a democratic society, enfranchising the entire population.[205] In such a utopian world there would also be little if any need for a state, which goal was to enforce the alienation.[171] He theorised that between capitalism and the establishment of a socialist/communist system, a dictatorship of the proletariat—a period where the working class holds political power and forcibly socialises the means of production—would exist.[205] As he wrote in his Critique of the Gotha Program, "between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat".[236] While he allowed for the possibility of peaceful transition in some countries with strong democratic institutional structures (such as Britain, the United States and the Netherlands), he suggested that in other countries in which workers can not "attain their goal by peaceful means" the "lever of our revolution must be force".[237]

Legacy[edit]

Marx's ideas have had a profound impact on world politics and intellectual thought.[10][11][238][239] Followers of Marx have frequently debated amongst themselves over how to interpret Marx's writings and apply his concepts to the modern world.[240]The legacy of Marx's thought has become contested between numerous tendencies, each of which sees itself as Marx's most accurate interpreter. In the political realm, these tendencies include Leninism, Marxism–Leninism, Trotskyism, Maoism, Luxemburgism and libertarian Marxism.[240] Various currents have also developed in academic Marxism, often under influence of other views, resulting in structuralist Marxism, historical Marxism, phenomenological Marxism, analytical Marxism and Hegelian Marxism.[240]

From an academic perspective, Marx's work contributed to the birth of modern sociology. He has been cited as one of the nineteenth century's three masters of the "school of suspicion" alongside Friedrich Nietzsche and Sigmund Freud[241] and as one of the three principal architects of modern social science along with Émile Durkheim and Max Weber.[242] In contrast to other philosophers, Marx offered theories that could often be tested with the scientific method.[10] Both Marx and Auguste Comte set out to develop scientifically justified ideologies in the wake of European secularisation and new developments in the philosophies of history and science. Working in the Hegelian tradition, Marx rejected Comtean sociological positivism in attempt to develop a science of society.[243] Karl Löwith considered Marx and Søren Kierkegaard to be the two greatest Hegelian philosophical successors.[244] In modern sociological theory, Marxist sociology is recognised as one of the main classical perspectives. Isaiah Berlin considers Marx the true founder of modern sociology "in so far as anyone can claim the title".[245] Beyond social science, he has also had a lasting legacy in philosophy, literature, the arts and the humanities.[246][247][248][249]

In social theory, twentieth- and twenty-first-century, thinkers have pursued two main strategies in response to Marx. one move has been to reduce it to its analytical core, known as analytical Marxism. Another, more common move has been to dilute the explanatory claims of Marx's social theory and to emphasise the "relative autonomy" of aspects of social and economic life not directly related to Marx's central narrative of interaction between the development of the "forces of production" and the succession of "modes of production". Such has been for example the neo-marxist theorising adopted by historians inspired by Marx's social theory, such as E. P. Thompson and Eric Hobsbawm. It has also been a line of thinking pursued by thinkers and activists like Antonio Gramsci who have sought to understand the opportunities and the difficulties of transformative political practice, seen in the light of Marxist social theory.[250][251][252][253] Marx's ideas would also have a profound influence on subsequent artists and art history, with avant-garde movements across literature, visual art, music, film and theater.[254]

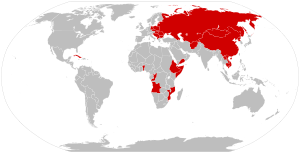

Politically, Marx's legacy is more complex. Throughout the twentieth century, revolutions in dozens of countries labelled themselves "Marxist", most notably the Russian Revolution, which led to the founding of the Soviet Union.[255] Major world leaders including Vladimir Lenin,[255] Mao Zedong,[256] Fidel Castro,[257] Salvador Allende,[258] Josip Broz Tito,[259] Kwame Nkrumah[260] and Thomas Sankara all cited Marx as an influence and his ideas informed political parties worldwide beyond those where Marxist revolutions took place.[261] The countries associated with some Marxist nations have led political opponents to blame Marx for millions of deaths,[262] but the fidelity of these varied revolutionaries, leaders and parties to Marx's work is highly contested and rejected by many Marxists.[263] It is now common to distinguish between the legacy and influence of Marx specifically and the legacy and influence of those who shaped his ideas for political purposes.[264]

'♣♣ 내 좋아하는 ♣♣ > Famous Lectures' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Premiere Pro Tutorial (0) | 2018.02.22 |

|---|---|

| * Movie Maker Tutorial (0) | 2018.02.22 |

| SEO techniques (0) | 2018.02.06 |

| President Trump's first official State of the Union address on Jan. 30, 2018 (0) | 2018.02.01 |

| EDWARD EVERETT's, GETTYSBURG ADDRESS (0) | 2017.12.14 |