The Communist Manifesto

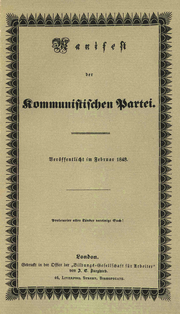

First edition, in German | |

| Author | Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | German (translated into several world languages) |

| Genre | Manifesto |

Publication date | 21 February 1848 |

The Communist Manifesto (originally Manifesto of the Communist Party) is an 1848 political pamphlet by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London (in the German language as Manifest der kommunistischen Partei) just as the revolutions of 1848 began to erupt, the Manifesto was later recognised as one of the world's most influential political manuscripts. It presents an analytical approach to the class struggle (historical and present) and the problems of capitalism and the capitalist mode of production, rather than a prediction of communism's potential future forms.

The Communist Manifesto summarizes Marx and Engels' theories about the nature of society and politics, that in their own words, "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles". It also briefly features their ideas for how the capitalist society of the time would eventually be replaced by socialism, and then finally communism.

Synopsis

| “ | A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism. | ” |

—Opening sentence | ||

The Communist Manifesto is divided into a preamble and four sections, the last of these a short conclusion. The introduction begins by proclaiming "A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre". Pointing out that parties everywhere—including those in government and those in the opposition—have flung the "branding reproach of communism" at each other, the authors infer from this that the powers-that-be acknowledge communism to be a power in itself. Subsequently, the introduction exhorts Communists to openly publish their views and aims, to "meet this nursery tale of the spectre of communism with a manifesto of the party itself".

The first section of the Manifesto, "Bourgeois and Proletarians", elucidates the materialist conception of history, that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles". Societies have always taken the form of an oppressed majority living under the thumb of an oppressive minority. In capitalism, the industrial working class, or proletariat, engage in class struggle against the owners of the means of production, the bourgeoisie. As before, this struggle will end in a revolution that restructures society, or the "common ruin of the contending classes". The bourgeoisie, through the "constant revolutionising of production [and] uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions" have emerged as the supreme class in society, displacing all the old powers of feudalism. The bourgeoisie constantly exploits the proletariat for its labour power, creating profit for themselves accumulating capital. However, by doing so the bourgeoisie "are its own grave-diggers"; the proletariat inevitably will become conscious of their own potential and rise to power through revolution, overthrowing the bourgeoisie.

"Proletarians and Communists", the second section, starts by stating the relationship of conscious communists to the rest of the working class. The communists' party will not oppose other working-class parties, but unlike them, it will express the general will and defend the common interests of the world's proletariat as a whole, independent of all nationalities. The section goes on to defend communism from various objections, such as the claim that communists advocate "free love", and the claim that people will not perform labour in a communist society because they have no incentive to work. The section ends by outlining a set of short-term demands—among them a progressive income tax; abolition of inheritances; free public education etc.—the implementation of which would be a precursor to a stateless and classless society.

The third section, "Socialist and Communist Literature", distinguishes communism from other socialist doctrines prevalent at the time—these being broadly categorised as Reactionary Socialism; Conservative or Bourgeois Socialism; and Critical-Utopian Socialism and Communism. While the degree of reproach toward rival perspectives varies, all are dismissed for advocating reformism and failing to recognise the pre-eminent revolutionary role of the working class. "Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Opposition Parties", the concluding section of the Manifesto, briefly discusses the communist position on struggles in specific countries in the mid-nineteenth century such as France, Switzerland, Poland, and Germany, this last being on the eve of a bourgeois revolution", and predicts that a world revolution will soon follow. It ends by declaring an alliance with the social democrats, boldly supporting other communist revolutions, and calling for united international proletarian action.

| “ | Working Men of All Countries, Unite! | ” |

—Closing line | ||

Writing

Friedrich Engels has often been credited with composing the first drafts which led to the Communist Manifesto. In July 1847, Engels was elected into the Communist League, where he was assigned to draw up a catechism. This became the Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith. It contained almost two dozen questions that expressed the ideas of both Engels and Karl Marx at the time. In October 1847, Engels composed his second draft for the League, The Principles of Communism (which went unpublished until 1914). once commissioned by the Communist League, Marx combined these drafts with Engels' 1844 work The Condition of the Working Class in England to write the Communist Manifesto.[1]

Although the names of both Engels and Marx appear on the title page alongside the "persistent assumption of joint-authorship", Engels, in the preface to the 1883 German edition of the Manifesto, said it was "essentially Marx's work" and that "the basic thought... belongs solely and exclusively to Marx."[2] Engels wrote after Marx's death:

I cannot deny that both before and during my forty years' collaboration with Marx I had a certain independent share in laying the foundations of the theory, but the greater part of its leading basic principles belongs to Marx ... Marx was a genius; we others were at best talented. Without him the theory would not be by far what it is today. It therefore rightly bears his name.[3]

Despite Engels's modesty in this quotation, he made major contributions to the Manifesto, starting with the suggestion to abandon "the form of a catechism and entitle it the Communist Manifesto." Moreover, Engels joined Marx in Brussels for the writing of the Manifesto. There is no evidence of what his contributions to the final writing were, but the Manifesto bears the stamp of Marx's more rhetorical writing style. Nevertheless, it seems clear that Engels's contributions justify his name's appearance on the title page after Marx's.[4]

'연구하는 인생 > Histrory' 카테고리의 다른 글

| U.S. Planned to Drop 12 Atomic Bombs on Japan (0) | 2015.08.16 |

|---|---|

| German nuclear weapon project (0) | 2015.08.16 |

| Paris Commune (0) | 2015.08.06 |

| First World War 1 년표 (0) | 2015.08.06 |

| Second world war 2 년표 (0) | 2015.08.06 |