Learning is a relatively permanent change in behaviour that marks an increase in knowledge, skills, or understanding thanks to recorded memories. A memory is the fruit of this learning process, the concrete trace of it that is left in your neural networks. Human memory is fundamentally associative. You can remember a new piece of information better if you can associate it with previously acquired knowledge that is already firmly anchored in your memory. And the more meaningful the association is to you personally, the more effectively it will help you to remember. So taking the time to choose a meaningful association can pay off in the long run. Also, contrary to the image that many people have of memory as a vast collection of archived data, most of our memories are actually reconstructions. They are not stored in our brains like books on library shelves. Whenever we want to remember something, we have to reconstruct it from elements scattered throughout various areas of our brains. Thus, scientists today view remembering not as a simple retrieval of fixed records, but rather as an ongoing process of reclassification resulting from continous changes in our neural pathways and parallel processing of information in our brains.

But memory has other characteristics than can make learning easier once you understand them. |

|

|

|

|

|

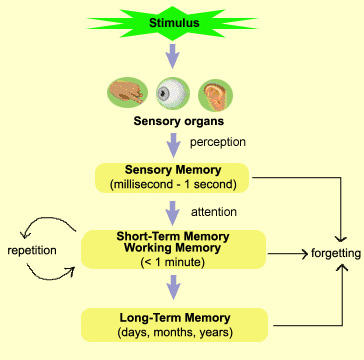

In the 1960s, the distinction among various types of memory according to their duration was the subject of passionate debates. Some scientists thought that the most elegant way to account for the data available at the time was to conceptualize memory as a single system of variable duration. But bit by bit, evidence accumulated that suggested the existence of at least three distinct memory systems. Though the mechanisms of these three systems differ, they do flow naturally from one into the other and can be regarded as three necessary steps in forming a lasting memory. According to this now generally accepted model, the stimuli detected by our senses can be either ignored, in which case they disappear almost instantaneously, or perceived, in which case they enter our sensory memory. Sensory memory does not require any conscious attention; as information is perceived, it is stored in sensory memory automatically. But sensory memory is essential, because it is what gives us the effect of unity of an object as our eyes jump from point to point on its surface to examine its details, for example.

Keeping an item in short-term memory for a certain amount of time lets you eventually transfer it to long-term memory for more permanent storage. This process is facilitated by the mental work of repeating the information, which is why the expression “working memory” is increasingly used as a synonym for short-term memory. But such repetition seems to be a less effective strategy for consolidating a memory than the technique of giving it a meaning by associating it with previously acquired knowledge. Once the piece of information has been stored in your long-term memory, it can remain there for a very long time, and sometimes even for the rest of your life. There are, however, several factors that can make these memories hard to retrieve. These factors include how long it has been since the event stored in your memory occurred, how long it has been since the last time you remembered it, how well you have integrated it with your own knowledge, whether it is unique, whether it resembles a current event, and so on. Many experiments still need to be conducted to assess the influence of each of these factors more closely. Nevertheless, we are beginning to gain a better understanding of the underlying systems necessary for each of these three types of memory to work properly. |

|

|

|

http://thebrain.mcgill.ca/flash/a/a_07/a_07_p/a_07_p_tra/a_07_p_tra.html#2

|

|

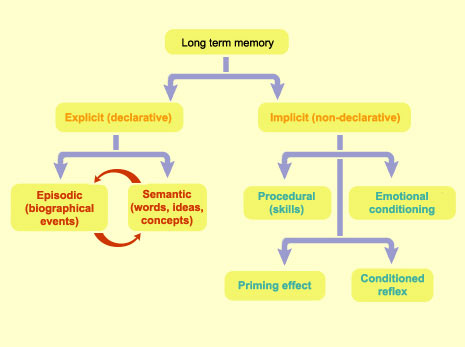

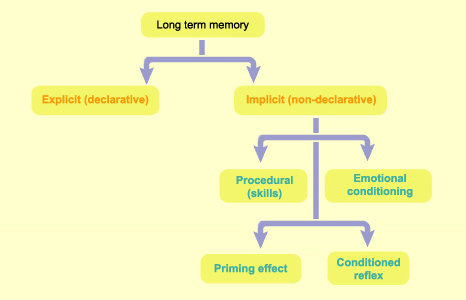

From a clinical and physiological standpoint, many observations suggest that there may be various sub-categories of long-term memory. For example, certain kinds of amnesia affect certain kinds of memories, but not others. Similarly, researchers have found that various brain structures specialize in processing various kinds of memories. One of the most fundamental of these distinctions is between declarative and non-declarative memory, based on whether the memory’s content can be expressed verbally. Traditionally, most memory studies have focused on explicit memory, which involves the subjects' conscious recollection of things and facts. For instance, subjects might be asked to memorize a given set of items (a list of words, a group of pictures, etc.) and then recall them verbally. Also, things that are encoded in implicit memory can be recalled automatically, without the conscious effort needed to recall things from explicit memory.

Perhaps the best known of the various types of implicit memory is procedural memory, which enables people to acquire motor skills and gradually improve them. Procedural memory is unconscious, not in the Freudian sense of suppressed memories, but because it is composed of automatic sensorimotor behaviours that are so deeply embedded that we are no longer aware of them. Patients with profound amnesia often retain their procedural memory, which argues for a system of separate neural pathways. Implicit memory is also where many of our conditioned reflexes and conditioned emotional responses are stored. The associative learning that constitutes the basis for these forms of memory is a very old process, phylogenetically speaking, and can take place without the intervention of the conscious mind. We form implicit memories without being aware that we are doing so. Hence, scientists who study such memories must often try to uncover them by indirect methods, such as "priming". In priming, researchers try to increase the speed or accuracy with which their subjects make a decision by first exposing them to information that relates to the same context, but without the subjects' having any other particular reason to retrieve the piece of information concerned. For example, subjects will take less time to decide that the string of letters "doctor" is a word if they have first been shown the word "nurse" than if they have first been shown an irrelevant word, such as "north", or a nonsense word, such as "nuber". Like implicit memory, explicit memory can be divided into subtypes - most often, episodic and semantic memory. |

'연구하는 인생 > Anatomy' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Shoulder anatomy (0) | 2013.10.19 |

|---|---|

| anatomy of human body animation (0) | 2013.10.14 |

| THE BRAIN (0) | 2012.03.03 |

| http://www.ithaca.edu/faculty/lahr/LE2000/LE_index.html (0) | 2011.06.05 |

| Nasal Cavity 鼻腔 Paranasal Sinus 副鼻腔 (0) | 2011.04.07 |